In its early years, amateur cinema displayed an affinity with the emerging avant-garde and experimental film movements (see “Amateur Cinema and Experimentation in the 1920s and 30s”). But by the mid-1930s, the amateur filmmaking community had largely disavowed formal experimentation. As a result, experimental films were featured less prominently in the major North American amateur film contests of the mid-1930s through the early 1950s. All the same, this period and the decades beyond would see some amateur filmmakers persist in the artistic endeavour of experimenting with film form.

In an effort to distance itself from the radical experimentation of the avant-garde, the Amateur Cinema League (ACL) offered limited praise to experimental films made after the mid-1930s. Maya Deren and Alexander Hamid‘s avant-garde classic Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) was one of few experimental works recognized in the ACL’s annual Ten Best contest during this period. In the ACL’s Movie Makers magazine, Meshes of the Afternoon was lauded for its “intelligent” experimentation that was accomplished without the use of image-distorting camera “gadgets” (Movie Makers, Oct. 1945, 406). The film experiments with the representation of subjectivity by employing dynamic camerawork, slow motion, extreme closeups, jump cuts, and multiple exposures – all of which contribute to an oneiric and foreboding tone. Deren also wrote articles for Movie Makers on creative and experimental approaches to amateur filmmaking, though her subsequent films did not appear in amateur film contests.

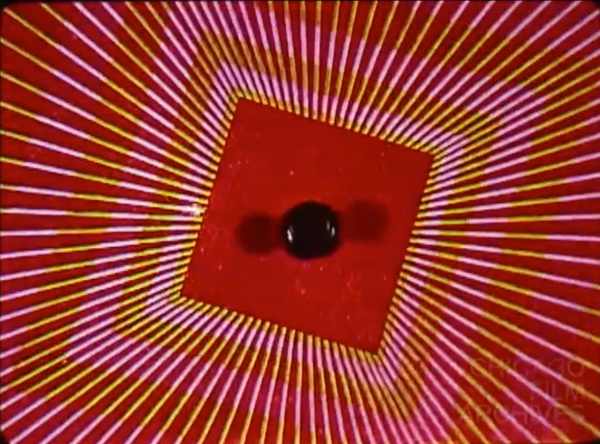

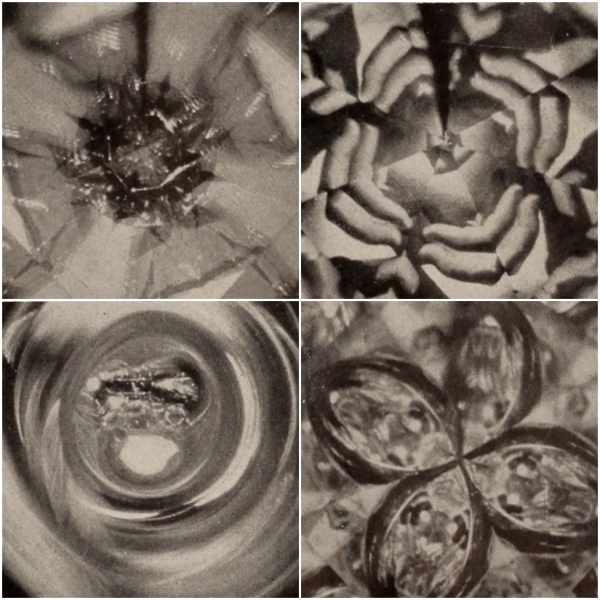

Despite the ACL’s apparent aversion to camera gadgets, Roberto Machado’s Kaleidoscopio (1946), an amateur film foray into visual music, won high praise and a place in the Ten Best of 1946. The film unified music and abstract images that Machado shot through a homemade lens attachment fashioned from a kaleidoscope. In addition, other experimental titles like Cine Whimsy (Robert Fels, 1942) and the Leonard Tregillus and Ralph W. Luce films No Credit (1948) and Proem (1949) earned acclaim in amateur film contests; still, this small assortment of films, along with the Deren connection, largely constitutes the ACL’s selective coverage of experimental filmmaking from 1935 to 1953.

Experimental amateur films were being made away from the ACL and its Ten Best contest in the 1940s and 50s. Amateurs across Canada, for example, were producing experimental films, and the Canadian Film Awards (CFAs) occasionally recognized such works in its amateur film category. At the second annual CFAs in 1950, the inaugural award for Best Amateur Film was presented to Claude Jutra for his experimental short Mouvement perpétuel (1949). As well, an avant-garde production titled Parking on This Side (1950) by the University of Toronto Film Society garnered an Honourable Mention at the CFAs in 1951. British Columbian filmmakers like Stanley Fox, and Oscar and Dorothy Burritt were also crafting award-winning experimental films in the 1940s. These works from Canadian amateurs demonstrate that the ACL’s views on experimentation were not wholly representative of the wider amateur filmmaking community in this period.

After 1953, the ACL’s Ten Best contest relocated to the Photographic Society of America (PSA), where experimental films reacquired consistent and unconditional award recognition. An impressive range of experimental works were recognized as part of the PSA Ten Best, which even presented a “Best Experimental / Abstract Film Award” in certain years. For instance, PSA Ten Best-winning films like Liquid Jazz (Joseph M. Kramer, 1962) and the George Lucas and Paul Golding student work Herbie (1965) deftly experiment with abstract visuals that evoke and move in synchronization with their soundtracks.

A film like Dear Little Lightbird (Leland Auslender, 1968) further exemplifies the creative range of an innovative approach to film form. Auslender’s film is an intimate reflection on the brief life of his son, and it blends home movie footage, scenes of art and nature, and still photographs with an emotional voice-over narration and several musical pieces by Mozart. The film’s formal choices, which also include the use of double exposure and an emphasis on abstract nature images, immerse the viewer in the “profound mystical experience” (Auslender, 2015) that the filmmaker is sharing. Dear Little Lightbird placed in the PSA Ten Best of 1968.

Amateur cinema showed varying levels of commitment to experimental filmmaking over the course of its history. The majority of the amateur film community chose to eschew experimentation after 1934, but some filmmakers remained drawn to the creative possibilities of formal experimentation in the decades that followed. This lasting dedication eventually saw experimental films regain a respected standing in the amateur film contests of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. Despite this wavering history, amateur cinema provided an array of experimental films which work to illustrate the diverse artistic nature of filmmaking.

Follow this link for a complete list of experimental amateur films on the AMDB.

Sources:

Auslender, Leland. Dear Little Lightbird (1968). YouTube upload, May 13, 2015.

Deren, Maya. “Efficient or Effective?” Movie Makers, June 1945, pp. 210-211, 224-226.

Deren, Maya. “Creative Cutting.” Movie Makers, May 1947, pp. 190-191, 204-206.

“Films You’ll Want to Show.” Movie Makers, October 1945, p. 406.

Machado, Roberto. “Adventures in Abstraction.” Movie Makers, May 1947, p. 195, 216-217.

Tepperman, Charles. Amateur Cinema: The Rise of North American Moviemaking, 1923-1960. University of California Press, 2014.