Amateur animated films illustrate the creative diversity of amateur cinema. Though most amateur filmmakers shot live-action films, amateurs also produced many artful and inventive animated films. Amateur works of animation exhibit a variety of animation techniques, including traditional (hand-drawn) animation, drawn-on-film animation, stop-motion animation, and clay animation. Using these techniques, amateur animated films range from live-action films that feature sequences of animation to abstract drawn-on-film works and even cartoons.

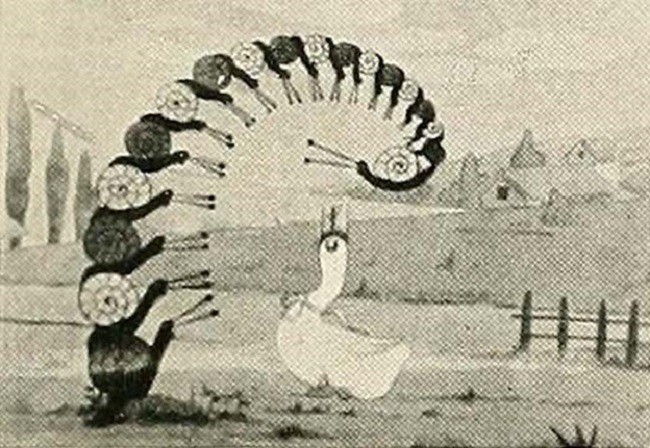

A 9.5mm film titled Walking of Baby Boy (1931) was the first animated film to be recognized in a major North American amateur film contest. The film earned Japanese animator Wagoro Arai a certificate award in the American Cinematographer Amateur Movie Makers Contest of 1932. Elsewhere, the Amateur Cinema League’s Ten Best contest, which began in 1930, would not recognize its first fully animated film until 1937, when Emile Gallet’s Ducky ‘n Busty (1937) was awarded a Ten Best - Honorable Mention. Movie Makers magazine reported that Gallet’s hand-drawn cartoon, which ran 400 feet, required over 4,000 hours of animation work (“Closeups—What filmers are doing”). Animated films, and the dedication they often necessitate, would continue to receive periodic award recognition throughout the lifespan of the major amateur film contests.

Animation was not restricted to those filmmakers who could contribute thousands of hours to their craft, however. Some amateurs enlivened their films by incorporating short sequences of animation into their live-action filming. Versatile amateurs could, for example, utilize this technique to add a comedic or fantastical element to their genre film, or to communicate information through animated diagrams in educational films. John and Agnes Thubron’s Her Second Birthday (1932) and Margaret Conneely’s Fairy Princess (1956) showcase the charming effect that a sequence of stop-motion animation can generate in an otherwise live-action film.

The amateur filmmaking community included prolific amateur animators. One such filmmaker is Canadian animator John Straiton, whose body of work features award-winning films produced in several different modes of animation. English animator Albert Noble also made elegant animated films in the 1960s, including the stop-motion masterpiece Button Ballet (1967). Furthermore, the renowned Scottish-Canadian animator Norman McLaren began as an amateur filmmaker while he was a student at the Glasgow School of Art in the 1930s. During his years as an amateur, McLaren made a number of award-winning experimental films, some of which were works of animation: see Colour Cocktail (1935) and Hell Unltd. (with Helen Biggar, 1937).

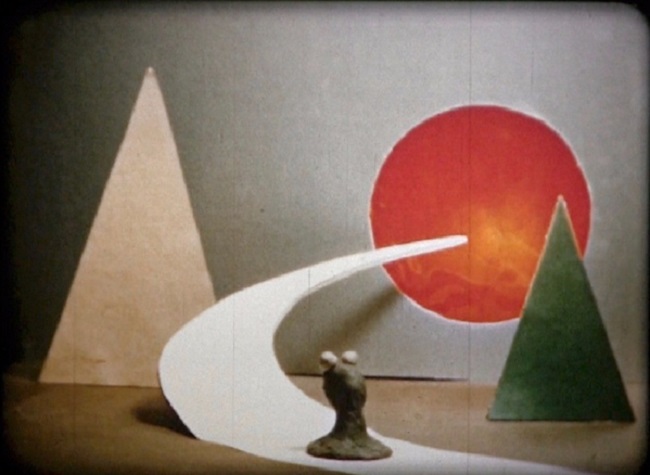

Animation’s boundless creative possibilities inspired amateurs to produce abstract and experimental animated films. For instance, Leonard Tregillus and Ralph W. Luce produced the well-regarded experimental clay animation films No Credit and Proem in the late 1940s. Meanwhile, other amateurs tested the abstract potential of the film medium through the technique of drawn-on-film animation. Sol Falon’s frenetic Dancing Colors (1968) visualizes this “direct” approach to film form, while Stuart Wynn-Jones’s Short Spell (1957) demonstrates a more playful application of the same technique.

Despite collecting only sporadic award recognition in amateur film contests, amateur animators produced an eclectic body of animated films. These films embrace an array of animation techniques, film forms, and film genres, and they collectively represent a prominent subdivision of amateur cinema.

Sources:

“Closeups—What filmers are doing,” Movie Makers, November 1937, p. 530.