During the 1960s and 70s two arms of amateur cinema emerged in Turkey: the individual endeavours and the group efforts. The term individual endeavours refers to non-commercial/non-theatrical short films made by a few enthusiasts, while the group efforts point out a radically politicized configuration of amateurism that shaped the collective efforts of filmmaking. Despite the differences, these two categories historically overlap with each other.

The individual endeavours of Turkish amateurism include the educational practices of then-filmmaking-students together with the personal records of historically significant events in the country. The cases of Alp Zeki Heper and Kaya Tanyeri illustrate those practices of the mid-century. When he was studying in Paris/France at IDHEC (Institut des Hautes Etudes Cinématographiques), Heper made two internationally awarded shorts that display the influences of surrealism. One of these surrealist films, L’Aube/Şafak [Down] (1962), questions the issues of becoming a couple along with the legacy of the patriarchal family unit (figure-1).

![L’Aube/Şafak [Down] (1962)](http://www.amateurcinema.org/images/uploads/afak.jpg)

With the rise of portable 8 mm and 16 mm cameras in the mid-20th century, a few amateurs in Turkey laid the groundwork for contemporary citizen journalism in the late 1960s and 1970s. Among those filmmaking enthusiasts was the pharmacist Kaya Tanyeri, who made the short documentaries of marches and protests reflecting the far-reaching impacts of May 68 in the country. Tanyeri’s 1 Mayıs 1977 [1 May 1977], for example, uses both the shots of police brutality that he recorded and the black-and-white photographs that depict the state-imposed violence during the May Day rally in Istanbul/Turkey (figure-2). The incident that Tanyeri’s amateur short film documented later became known as Kanlı 1 Mayıs (the “Bloody First of May”) in the country.

![Figure 2: 1 Mayis 1977 [1 May 1977]](http://www.amateurcinema.org/images/uploads/1_May%C4%B1s_1977.jpg)

The individual endeavours of amateur filmmakers did not only exhibit the works of live-action cinematography. The personal practices of amateur cinema also include one of the earliest animated short films in the history of Turkish film. In 1969, a friendship-turned-collaboration between an art historian and a magazine caricaturist resulted in the Âmentü Gemisi Nasıl Yürüdü? [How Was the Âmentü Ship Steered?] (figure-3). Dr. Sezer Tansuğ and Tonguç Yaşar’s animation film, embellished with the monochrome drawings (a reference to the Ottoman calligraphy) satirizes a well-known Alawi/Islamic myth in Turkey. One distinct characteristic of the animated short is the voice-over narration of an eponymous poem, accompanied by the melodies that emulate the Turkish classical music (Gemuhluoğlu). Indeed, the collaborative effort between two amateurs that produced How Was the Âmentü Ship Steered? points out a larger trend in the late 1960s.

![Figure 3: Amentü Gemisi Nasıl Yürüdü? [How Was the Amentü Ship Steered?]](http://www.amateurcinema.org/images/uploads/Ament%C3%BC_Gemisi_Nas%C4%B1l_Y%C3%BCr%C3%BCd%C3%BC.jpg)

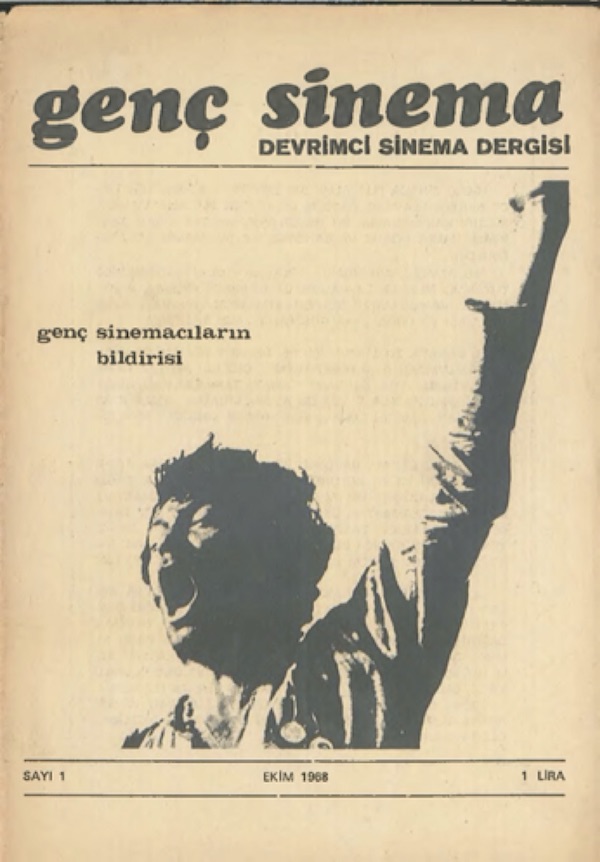

The group efforts of amateur cinema practices in the 1960s and 1970s, lead to two film collectives in Turkey: Genç Sinema Grubu (the “Young Filmmakers Group/YFG,” 1967-1971) and Halk Sineması Grubu (the “People’s Cinema Group/PCG,” 1978) (Akser). Organized around Sinematek Derneği (the “Cinematheque Association”) in Istanbul, the thirty young amateur cineastes with dire economic hardships created an avant-garde movement that paved the way for present-day video activism in Turkey (Candan). The unique characteristic of the YFG is that the Group came to intersect with the Third Cinemas of the Global South and the French Cinéma Militant of the mid-20th century (Orsler and Croombs). This intersection that amalgamated documentary modes with the narrative film especially drew from the ideas and practices of Latin American filmmakers at the time like Glauber Rocha along with that of Les groupes Medvedkine (and the key Soviet avant-gardes). The aggressive spirit of militant/third cinema and the chaotic socio-political atmosphere in mid-century Turkey also led the YFG to embrace a radically politicized form of amateurism as a weapon necessary to fight the guerilla war against the country’s once-dominant cinema industry—Yesilçam (literally, the “Green Pine”). The young filmmakers’ periodical, Genc Sinema Devrimci Sinema Dergisi (the Young Cinema: Revolutionary Cinema Journal, 1968-1971), worked to apply theoretical ideas to counter-cinematic practices simultaneously (figure-4) (Yıldız). Many amateur short film contests helped them constitute their independent distribution networks as well. [One of the YFG members, İbrahim Bergman, summarizes the reasons behind the Group’s embracement of a radically politicized form of amateurism in his essay, “The Art Event and The People,” which was published in the second issue of Young Cinema. A translation of Bergman’s manifesto is presented below this article.]

After the YFG’s dissolution in the wake of the 1971 Turkish military memorandum, another film collective associated with amateurism and militancy, the PCG, took up where the young filmmakers left off. The PCG’s only known short amateur documentary, the Turkish-Canadian filmmaker Ishak Işıtan’s 2 Eylül Direnişi [Resistance of September 2] (1978), is the only audio-visual record of the eponymous incident—significant for the history of the socialist movement in Turkey today.

Although both these individual endeavours and group efforts illuminate an early period of amateur filmmaking in Turkey, they ultimately represent an incomplete picture of this rich amateur cinema culture. One particular missing piece in this intricate picture of non-professional filmmaking are home movies. Some autonomous archivists in the country preserve large collections of home movies, such as Ege Berensel’s Turkish Family Films Archive which consists of 8 mm amateur shorts made in the 1960s/70s. The next step to fill the space of home movies in attempting to rewrite the history of cinema in Turkey and beyond should be bridging the gap between archivists/collectors and academe.

References

Akser, Murat. “Turkish Independent Cinema: Between Bourgeois Auterism and Political Radicalism.” In Independent Filmmaking around the Globe, edited by Doris Baltuschat and Mary P. Erickson, 131-148. University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Bergman, İbrahim. “Sanat Olayı ve Halk.” Genç Sinema 2, (November 1968): 9-11.

Candan, Can. “Documentary Cinema in Turkey: A Brief Survey of the Past and the Present (2014).” In The City in Turkish Cinema, edited by Hakkı Başgüney, and Özge Özdüzen, 113-134. Istanbul: Libra Yayinlari, 2014.

Gemuhluoğlu, Zeynep. “How Was the Âmentü Ship Steered?,” Accessed January 4, 2019. https://www.tsa.org.tr/en/yazi/yazidetay/67/%EF%BF%BDmentu-gemisi-nasil-yurudu

Orsler, M. Mert, and Matthew Croombs. “The Simple Image: on the Internationalism of Radical Amateur Filmmaking in Turkey.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 37 (8) April 2020.

Yıldız, Esra. “Lost Images, Silenced Past.” In The Politics of Culture in Turkey, Greece & Cyprus: Performing the Left since the Sixties, edited by Leonidas Karakatsanis, and Nikolaos Papadogiannis, 142-162. Basingstoke: Taylor & Francis, 2017.

In the formation of an art event, accessing the people is one of the most significant factors. Every work of art inaccessible to the people or each piece of a composite artwork that the people do not welcome in one way or another cannot escape the cage of time, which will ultimately decay and decompose that work. In contrast, the accepted art events will increase their aesthetic value by the number of people who embrace them.

In a country where 40% of the population is illiterate and the remaining 60% do not really comprehend what they read and write, it is highly unlikely that a dense theoretical piece of writing, for instance, will be fully understood by the people for whom it sought to build a better future.

Why Cinema?

When we briefly have a look at the other branches of the arts, we can see that the only branch with the potential to reach out to the large masses of people in Turkey is cinema.

For the man of letters, whose artworks might well speak at the masses, the power of literature to inspire people is a question. Further, the revolutionary literature, with its elite audience and the problem of accessing the people, is subject to forms of censorship. The only genres that have reached out to the masses are the folk poem and the folktale, basically, the folk literature, which stems from the people themselves. However, instead of being enriched and used by the country’s progressive movements, the power of folk literature is intentionally limited, lowered, and humiliated in the eyes of the people.

It might be presumed that painting and sculpture that are aesthetically pleasing in nature have the opportunity to speak to the people who are illiterate or semi-literate. But it is misleading to see plastic arts as the true medium of communication that can incite revolutionary action. Above all, today’s painters in Turkey, under the heavy influence of the West, cannot escape imitating the West.

Regarding music, it is a fact that Turkish people do not listen to Turkish classical music. (Even if they do, there is no revolutionary hope in it.) Other genres are not much different from classical music. There only remains Turkish folk music, which has already been demonized in the eye of people just like folk literature.

Similar to every underdeveloped country, the two branches of arts with the most promising potential to access people are cinema and theatre. The people either in the theatre hall or in the movie house, where they can comfortably sit and watch, enjoy these mixed arts on the pretext of entertainment, and they are impressed by what they see and hear there as well.

For a well-prepared theatre play, the artist needs at least a month or more. But, in a month, the Turkish filmmaker can make a feature-length film or a few short films. In terms of budgeting, the expenses related to costume, setting, and actors are more or less the same as a theatre play. (With the financial resources needed for My Fair Lady staged at the state theatre, an expensive film production would even be possible in the professional film industry.)*

With all its powerful capabilities and promising potential to impress and directly influence the people, cinema as an art form should be separated from the other branches of the arts and needs to be the first, natural choice for every artist to create social art.

Why Amateur Cinema?

First and foremost, the cinema is a new branch of the arts, and it has not yet been fully explored so far. Thus, despite the professional film industry - a prime example of cultural degradation - there is still hope for a better cinema. This form of cultural degradation should and will stop speaking for cinema sooner or later. The people have already got tired of the practices of the professional film industry, whose daily job is to circulate the repetitions of the same formulas and outputs without aesthetic concerns. Today, the producers have difficulty relying on even their well-known excuse: “people want them.” Indeed, with all the clichéd images and narratives, the professional film industry has always been far away from representing the real, the social problems of the people. The main reason behind the people’s interest in the outputs of the professional film industry, however, is the fact that cinema is the most economical form of entertainment that they can afford to experience.

Within the realm of the professional film industry, there seems to be no effort to represent the social reality of the people. Additionally, due to the class status of the professional film industry’s producers, it is too utopian to expect so. Their cultural knowledge, their intellect, and their aesthetic conceptualizations are not even sufficient to meet the needs that representing the people’s reality requires as well. Hence, demolishing such a cinema of degradation and recreating the art of cinema depicting the societal reality is the goal of an amateur filmmaker.

When the impact of the individual artist on society is taken into account, the amateurs of all branches of the arts seem to have the power to set the contemporary agenda of the art world and to offer a set of new directions for the future. Because cinema is the branch with the most powerful capabilities and potential to influence and inspire the people, the amateur cinema of Turkey has one goal to achieve: to shape and reshape the future of both cinema and the people in the country.

The Responsibilities of an Amateur Filmmaker

Within the artistic realm, cinema appears as the most economic and reasonable branch of the arts to create, considering especially the number of people it can reach. The most efficient way of reaching out to the people, the cinema, can also be brought to the people easily. But we, the amateurs, should utilize it very carefully and purposefully.

We need to avoid any abstractions in the name of our caprice, hubris, as well as our selfish benefits and interests. A highly ambiguous and fully symbolic film grammar might even surprise a small number of people and attract their attention.

Our goal is to make films about the problems of the people for the people; the ones who will be watching our works should be able to understand their meanings. We also need to show modesty by visiting the people and screening our films at their convenience.

Our purpose is to introduce the people to the cinema that represents societal values, their values. Only then will our cinema be accepted and appreciated by the people.

We, the amateur filmmakers, must be the guerilla of the artistic realm of Turkey.

Sharpening the gaze and the judgment of the people, and directing them to the future, within the realities of Turkey, is possible only through cinema. The only branch of the arts to help to achieve such goals is cinema. In creating the future of Turkey, the cinema is the most effective element together with the revolutionaries of cinematic art: the amateur filmmakers. There should be no doubt about it.

We must remember that we, the young amateur filmmakers, are working with such a significant artistic instrument and should never deviate from the direction of our goals.

Notes

* The translator uses the phrasing, “the professional film industry,” instead of using the Turkish word, Yeşilçam (literally, the “Green Pine”), which is a metonym referring to the professional film industry of Turkey in the 1960s and 1970s (and beyond).